Literature

In addition to a rich, oral vernacular, in Georgia early church literature was developed under Byzantine influence; the oldest manuscript is from 864. The advent of a Georgian nation state in the early 12th century brought a cultural boost. During Queen Tamar’s reign (1184-1212), court poetry and the knight novel flourished, and Sjota Rustaveli wrote his heroic poem “The Knight in the Tiger Traps” (not in Swedish translation) which became Georgia’s national epic. Towards the end of the 1600’s, Sulchan-Saba Orbeliani expressed his ideas of enlightenment in the writing “Wisdom of the Wisdom” (not in Swedish translation).

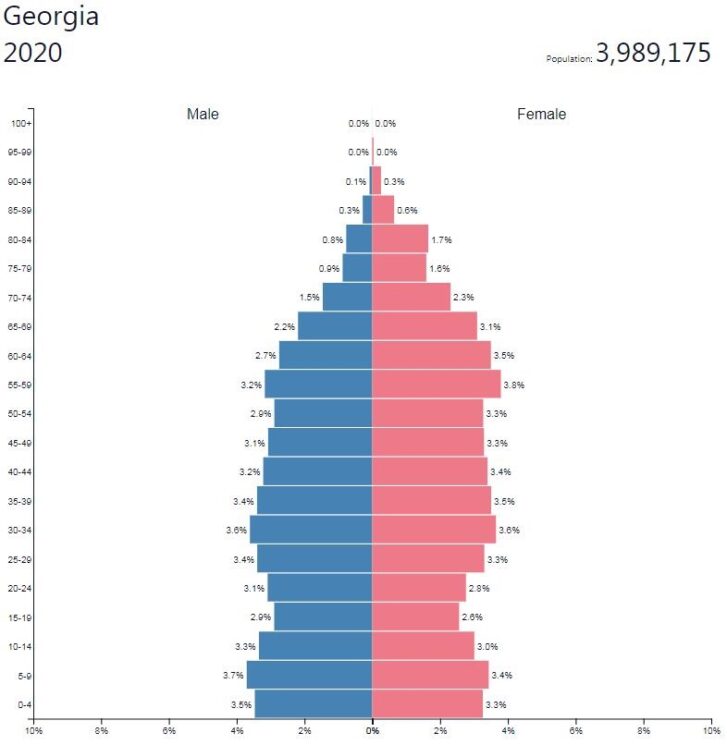

- Countryaah: Population and demographics of Georgia, including population pyramid, density map, projection, data, and distribution.

Since Georgia’s accession to Russia, during the 19th century, the national romantic lyric was represented mainly by Nikoloz Baratajvili and Aleksandre Tjavtjavadze. Ilia Tjavtjavadze developed an effective social criticism in her poetry and essay. At the same time, Akaki Tsereteli was very productive, who in poetry, songs, dramas and prose works intertwined the social and national motives for freedom.

A modern classic in Georgian poetry is Galaktion Tabidze, whose support for Soviet political ideals did not prevent him from renewing lyric to both theme and form. Near the symbolism stood the two poets Titsian Tabidze and Paolo Iashvili, who had good contacts with Russian modernists, mainly Boris Pasternak. (Both Tabidze and Iashvili were shot during the Stalinist purges.)

A later lyricist is Irakli Abasjidze, who drew inspiration from Rustaveli for his highly optimistic poetry. Modern Georgian prose is represented, among others. by Tjabua Amirjibi, whose novel “The Outlaw” to the hero has the legendary Data Tutashchia, a Georgian Robin Hood from the 19th century.

Film

The Georgian film is renowned for its creativity, artistry and professionalism and contributed greatly to the good reputation of the Soviet Union as a film country.

Shortly after the turn of the century, Aleksandr Digmelov was responsible for short films about local news, and in 1912 Vaso Amasjukeli made the first documentary, about the poet Akaki Tsereteli. The creation of a film laboratory in Tbilisi in 1918 allowed regular film production. The first feature film based on Georgian script and with Georgian actors was made in 1920, “Arsen Dzhordzhiasvili”, about the 1905 revolution. In 1921, Soviet power was established in the country. Among the filmmakers of the 1920’s belonged, among other things. Georgia Makarov, Aleksandre Tsutsunava and Ivane Perestiani. In terms of production, classic film formations, comedies and political doctrines dominated. The film climate was generous: in 1926 only 12 feature films were made. Towards the end of the decade, new director names were added such as Kote Mardzhanichvili, ethnographer Siko Dolidze, Micheil Kalatozyshvili (later known as Kalatozov) and Nikoloz Sjengelaia. Among the most popular films was the latter’s tragic love drama “Eliso” (1928).

The audio film followed two fruitless decades in the characters of the Stalin cult. Career now made filmmakers like Micheil Tjiaureli, as with “Chabarda!” (1931), against moral decadence, and his subsequent films demonstrated that he followed the new ideological requirements.

Apart from Tengiz Abuladzes and Rezo Tjcheidzes in Cannes’ award-winning “Magdana’s Ass” (1955), it was only towards the end of the 1960’s that the Georgian film again achieved success, even internationally, with films characterized by both formal and thematic complexity. Among the leading representatives were the brothers Shengelaia, sons of Nikoloz, Eldar with satirical comedies such as “The White Caravan” (1963) and Giorgi with a more lyrically embossed work, further Otar Ioseliani, driven in exile by the authorities, the versatile Georgia Danelija, documentary filmmaker Lana Gogoberidze with “The day is longer than the night” (1984), the Tbilisi-born Armenian Sergei Paradzjanov, who made his last two films here, and until his death in 1994 Abuladze, who with “Penalty” (1984) accounted for it the first anti-Stalinist work.

After independence, Georgia has had difficulty establishing a continuous film production.

Art

Finds of metal jewelry and pottery from the second millennium BC shows that Georgian art and crafts have a long tradition. In particular, metalwork has emerged as a national branch of art. With the country’s Christianity in the 300’s, Georgia became part of the Byzantine cultural sphere. Nevertheless, there are clear national characteristics, both in style, material and motivational details. There are also considerable differences in relation to the similarly Christianized neighboring Armenia in the 300’s.

The richest development applies to works in silver and cloisonn谷 enamel, icons, book binders, crucifixes and others (procession crosses from Breti, 994-1001, icon with Simon Styliten, 1015, tondo with Holy Mamaj, 1000’s, Chachuli icon, 900 -1100 number). The mural painting, the mosaic (Tsromi, 600’s, Gelati, 1100’s) and the book painting are characterized by Bysans by a different color scale and a distinct linear style. Reliefs in stone, i.a. on the facades of the churches, is often found.

It was not until the 19th century that an easel painting and a more realistic style developed. The founder of modern Georgian painting is Giorgi Gabashvili (1862-1936). Other significant artists are Mose Toidze (1871-1953), sculptor Iakob Nikoladze (1876-1951) and Davit Kakabadze (1889-1952), who in the 1920’s participated in the avant-garde Paris. A special position takes the internationally renowned autodidact Niko Pirosmani (also Pirosmanashvili 1862-1918).

Architecture

The earliest architecture in Georgia shows connections to the Hellenistic world and to the east. The church building developed from the 400’s has a relationship with both Byzantine and Armenian architecture. The main type was the cruciform plan with a dome on a high drum covered with a conical roof. In Mtscheta there are several significant churches both from the first Christian era and from the second cultural flourishing of the 1000’s, the latter with rich ornamentation in stone.

The older housing construction in Georgia shows several characteristic types, such as the caves cut into the Vardzia caves or densely built mountain villages with defense towers on several floors. An older type of dwelling is a darbazi with pyramid-shaped wooden roof, supported by an often ornate center pillar.

From the Soviet era, there are only a few buildings with regional characteristics. The heavily hilly terrain has motivated terrace houses and some occasional experiments with point houses interconnected in the upper floors.

Music

With Georgia’s Christianity 337, a multi-part vocal liturgical music developed from ancient ritual practice that influenced church music throughout Eastern Orthodox Christianity. During the Georgian high culture 900-1100, high level poetry, literature and music were developed. Cosmopolitan Tbilisi became the region’s cultural center early on. Persian, Turkish, Azerbaijani and Western European art music was grown, and touring music groups from East and West performed. This resulted in a distinctive urban music tradition.

From the 19th century, a concert system developed after Western role models, with music schools, opera (1821) and philharmonic orchestra (1905). Art music is strongly influenced by the rich folk music traditions. through works by Zakaria Paliasjvili (1871-1933), Dimitri Araqishvili (1873-1953), and Meliton Balantjivadze (1862-1933), father of the famous choreographer George Balanchine (Balantjivadze). Among the composers of the 20th century are notably Otar Taktakisjvili (1921-89) and Gia Qantjeli (born 1935).

Folk musical aesthetics are characterized by an emphasis on improvisation and the avoidance of repetition. A highly developed and very complex folk vocal multiplayer was developed early and exhibits many archaic features, especially in the mountain regions. The popular collective singing is very widespread and is usually performed by men and women individually. A type of song, common in eastern Georgia, has a soloist melody (the middle part) and treble on top of a collectively performed bass. Another type, scattered in western Georgia, has three or more independent voices, in some neighborhoods with the addition of an iodine-like embroidery treble (Crimean July). The instruments are many and often put together in small ensembles. Popular in the countryside are long-neck ends (panduri and thonguri)), bagpipes (goddess virus) and flute (salamuri), and in the cities, among others. duduki (of oboe type) and daira (frame drum). Dance music has been performed mainly on special Caucasian accordions and two-fold drums (doli) since the 20th century. Also the dance art is highly developed, with soloist, equilibristic toe-tapping dances (including lekuri) and collective ring dances (perchuli).

During the 19th century, popular music was developed in cities such as Tbilisi and Kutaisi, with influences from Russia and Western Europe, including a very popular urban singing style, performed by trios for guitar accompaniment. From the 1880’s, public concerts with folk music became very popular. During the 1930’s, Russian-style music schools were set up all over Georgia.

With Soviet cultural policy, folklore ensembles, festivals and a corps of professional choirs with 7-12 male singers were introduced. Among the most well-known, both in Georgia and abroad, during the post-war period included Gordela, Rustavi and Pazisi. From the 1960’s Western European music forms such as jazz, pop and rock have gained a foothold, often with strong domestic character. World famous in the 1970’s became the song group Orera, which united Georgian folk tradition with modern European popular music. Since the 1990’s, interest in Georgian folk and liturgical multi-voice singing has increased both in Georgia and throughout the world.