Apart from the censorship, the novel of manners had not been able to assert itself in Yedo, both because the intellectual element prevailed here, among which the tradition of good literature was alive and therefore lacked a taste for the obscene, and also because it he found himself competing with other genres that ended up taking over. First, among these, the jitsurokumono “authentic relations”, a kind of historical paraphrase, in which the historical element is treated in such a way as to leave the field free for the imagination. War adventures, discord of noble families, bloody vendettas, the lives of illustrious men are the most common subjects, and the style, usually simple and unadorned, gave them wide popularity. The best known of them remained the Ō oka Meiyo Seidan(The glorious judgments of Ōoka) collection of 43 famous cases educated by the famous Ōoka Tadasuke (1677-1751), judge and governor of Yedo known for the Solomonic wisdom of his judgments. The Jitsuroku – mono were prohibited in 1804, as insulting to the fame of Ieyasu, but they continued to circulate secretly in manuscript.

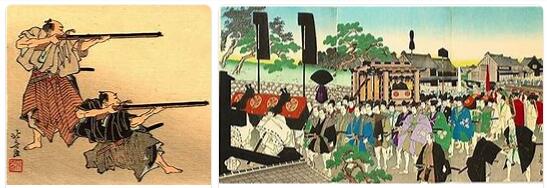

A genus whose precursors can already be glimpsed in some kana – z ō shi, had meanwhile become individualized and had established itself from the Genroku era (1688-1703) onwards with the so-called kusa – z ō shi (miscellaneous), to the people, at first short (5 pages), then longer, until they become very voluminous and said, depending on the color that fashion, hand in hand with the extension of the story, made their cover assume, aka – hon (red books), the shortest ones, then kuro – hon (black l.), ao – hon (green l.), ki- by ō shi (yellow l.) and finally g ō kan – mono (united l.). Their characteristic are the illustrations, made by men often famous in art, such as Hokusai and Utamaro. Beginning with a series of fairy tales for children, even today read avidly by the small world, the kusa – z ō shi gradually took on the physiognomy and extension of the novel to include stories of love, revenge, rivalry and the like. The best writer of them is considered Ryūtei Tanehiko (1783-1842), a man of scholarship and multiform talent, whose masterpiece, Nise Murasaki Inaka Genji(A pseudo Murasaki and a rustic Genji, 1829-42), is an imitation of the Genji Monogatari in which the action is carried to the shōgun’s court. Some stories of him still need to be remembered which, being largely dialogued in the manner of dramas, were called sh ō honjitate (from sh ō hon “script” and shitate “composition”).

According to ezinesports, an important moment in the evolution of the kusa – zoshi is represented by the reduction of the illustrations to the advantage of the length of the text, which thus acquires greater importance. The Japanese give the name yomi – hon (reading books) to this category of writings. Moreover, they are always novels, which however reveal a tendency towards morality and therefore constitute a more noble genre, often with an educational character that will end up taking on epic traits. Among the first yomi – hon must be counted the Kokin Kiden Hanabuser – z ō shi(Florilege of curious and modern stories, 1749) by Kinro Gyōja, the Nishiyama Monogatari 1768), by Takebe Ayatari (1718-1774), written in a pure but ancient language in which the influence of the style is manifested with the philologist archaizing by Mabuchi and Ugetsu Monogatari (Tales for the rains and moonlit nights, 1708) by Ueda Akinari (1732-1809), also a philologist and admirer of Mabuchi. But dii: maiores of the yomi – hon must be considered Santōan Kyōden (1761-1816) and Bakin.

Santōan Kyōden made his debut with some share – bon, but, having won prison at the time of the institution of censorship, he later started writing sensational novels full of exciting and terrible situations that appeared as yomi – hon. His masterpiece is considered the Mukashigatari Inazuma By ō shi (Flash cover of old stories, 1805) which had a delusional reception by the crowds and was dramatized in Ōsaka. Kyōden’s style is flat, imaginative and attractive, and left a permanent imprint in later literature.

His pupil, the very fruitful Kyokutei Bakin is considered by his compatriots to be the greatest novelist. Of his 290 novels, of which only a few in one volume, the Japanese consider the Hakkenden or “Story of the Eight Dogs” his masterpiece, an endless story in 106 volumes on which he worked for twenty-eight years and which aroused real enthusiasm, whence requests that the numerous editions of his are intended to end up raising the price of paper. In reality, it is a very intricate plot of fantastic, impossible, extravagant adventures of eight knights personifying the eight Confucian virtues. European critics define Hakkenden as “soporific”, and instead consider Chinsetsu Yumihari as the best work – zuki(Wonderful Story of the Crescent Moon, 1810) which tells the adventures of the famous archer Minamoto no Tametomo (1139-1170). Bakin’s only advantage is his flowing, expressive, harmonious style; his works are also immune from obscenity or vulgarity and the sentiment is always high, but the psychological and artistic side is lacking or scarce. The badly outlined characters, the sketchy and lifeless scenes, the artificial sentiment, the prevalence of the fantastic and the portentous, the lack of spirit of observation and sense of the reality of life are the main defects. Bakin works with the mind, not the heart; develops the action, not the characters; his Confucianist conception of the world makes him create rigid and conventional types, ideal figures from the point of view of Confucianist morality.

The first years of the century XIX saw the emergence of a new genre, the comic novel (kokkei – bon), thanks to two bizarre spirits who have linked their name to it: Jippensha Ikku (1765-1831) and Shikitei Samba (1775-1822). Of the 311 writings of the first, the Hizakuri – ge (On horseback, 1822) is very important, in 56 volumes, which narrates the comic adventures of a journey on the Tōkaidō, and is also important because it preserves precious folkloristic memories and as a collection of ancient “farces”. More realistic than Ikku, Samba in his two works Ukiyo – buro (Bagno mondano, 1809-13) and Ukiyo – doko(Worldly barber, 1811) has left us a series of very lively scenes in which individuals typical of every social sphere talk, agitate, discuss, gossip, from the scholar to the ignorant, from the noble to the peasant, from the geisha to the housewife. His spirit is even finer than that of Ikku, and although he is sometimes in the vulgar, he is rarely obscene.