Epoch of indigenous laws. – It goes from the legendary foundation of the empire, in the sec. VII a. C., until the end of the VI century d. C. In this era, Japanese society has a patriarchal basis, the political and social unity is the clan, each clan has its own task; over all clans the emperor predominates, whose family is the primeval clan, to which the others are subjected.

Epoch of the adoption of the Chinese law system. – It goes from the beginning of the century. VII until the end of the century. XII. The adoption of the Chinese system of law was the work of the imperial power itself, which, seeing itself threatened by the clans that had become excessively powerful, carried out what could be called a real revolution, if it had not been carried out by the legitimate authority: introduced the Chinese constitution, abolished clans and their privileges, expropriated their lands, forfeiting them to the crown, etc. However, the country was far from possessing those conditions of progress and civilization which in China had allowed the surprising development of law under the T’ang dynasty (618-907). So that the reform was imposed as long as the imperial power that had introduced it remained strong politically and militarily, but with its weakening, the reform found formidable obstacles in the very situation of the country, and, over time, contributed, on the contrary, to form and consolidate feudalism. In this second period there were the first codifications of laws. These to “criminal rules”ry ō “civil norms” kaku are the complementary ordinances, issued after the codification, and shiki are the administrative orders and rituals of feasts and ceremonies. The first Japanese code, called Ō mi-ry ō, completed in 689, after more than thirty years of preparatory work, was completely modeled on the Chinese code and included 22 books of ry ō, but it has not survived, nor is it it was clear whether or not it contained criminal law. It was replaced in 701 by the famous “Code of the Taihō era”, the Taih ō ritsu – ry ō. This code, the work of Emperor Monmu (697-707), remained formally in force until the imperial restoration in 1868. In the following two centuries there were then three important codifications of kaku and shiki, namely the K ō nin – kaku – shiki, published in 1811, the J ō gztan – kakushiki in 1868 and the Engei – kaku – shiki in 1907.

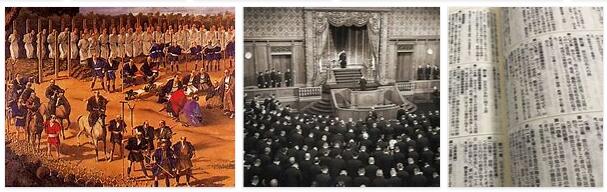

Mixed era of indigenous and Chinese law. – According to sunglassestracker, it goes from 1192 to 1868. This period includes the shogunal regime of the Minamoto, the regency of the Hōjō, the shogunate of the Ashikaga and that of the Tokugawa. This long period, of about seven centuries, is divided into three minor periods, namely: 1192-1477, Period of the capitulars ; 1477-1615, period of the laws daimy ō nali ; and 1615-1867, period of the ordinances. Among the most important legislative manifestations of this era are to be noted: for the period of the capitulars, the J ō ei shikimoku or “The capitular of the Jōei era”, promulgated in 1232, during the regency of the Hōjō (1205-1333), and containing 51 chapters; theKenmu shikimoku or “the capitular of the Kenmu era”, promulgated in 1356 during the shogunal regime of the Ashikaga (1338-1573); for the period of the daimyōnali laws, the Jinkai – sh ō, “Code of the daimyōnale house of Dates”, compiled around 1535; and finally for the last period of the ordinances, note the three famous codes promulgated in 1615 by the founder of the Tokugawa power himself: the Buke shohatto, code for the military, the daimyō and the samurai; the Kuge shohatto, code for the princes and nobles of the court, and the S ō ke shohatto, code for ecclesiastics. During the long and peaceful Tokugawa shogunate, all legislation received a new and vigorous impetus, and considerable attempts were made to settle it. The very numerous provisions issued during this period were brought together, depending on the subject, in the first years after the imperial restoration, to serve as study material for the preparation of the codices, forming the powerful collection entitled Kwaj ō ruiten. Characteristic of the legislation of this period is that it was not made public, but only communicated confidentially to the judicial and administrative authorities that had to apply it.

Epoch of the adoption of European and American law. – It begins with the imperial restoration (1868). Immediately after the abolition of the shogunate, a pure and simple return to Chinese laws was attempted, which twelve centuries earlier had been introduced by the imperial power itself; but, by now, the grandiose events which had led to the restoration of feudalism and to regular relations with the European powers, required more radical reforms. A movement for the adoption of the laws of Western countries found valid support in the ruling class itself, and had the upper hand. Japan, in a few years, gave itself a new legislation, modeled on those of the most advanced European powers.