The oldest traces of settlement in the United Arab Emirates (FAE) date from the Neolithic period, around 5500 BCE. – when the climate was more humid, and access to food much better than today. New archaeological finds at Jebel Faiyah in Sharjah indicate that the first people may have come to the area already in Paleolithic times – at least 100,000 years ago. Excavations in this area attest to activity in both the Bronze Age and the Iron Age.

The Al-Bidya towers in the emirate Fujairah, estimated to date from the mid-1400s.

Ancient

From the Hafit period, circa 3000–2500 BCE, traces of joint burials from Jebel Hafit have been uncovered in today’s Abu Dhabi. In the subsequent Umm al-Nar period, around 2500–2000 BCE, the first oasis communities were established with circular forts built of stone.

Already from the first settlement there are traces of contact with the outside world, especially civilizations further north, where the inhabitants probably traded with copper from Hajar. For the next millennium, trade became central to the development of the area – up to modern times and today’s modern society. During the Wadi Suq period and the Bronze Age, in the period 2000–1300, trade with Dilmun in today’s Bahrain was developed. Societies in the later FAE became involved in extensive trade, eventually using caravans, with Mesopotamia and Syria, then linked shipping to Iran, among others., Baluchistan and the Indus civilization. Next to copper was the most important export commodity – for several millennia; until the 20th century – pearls.

The domestication of the camel for livestock, towards the end of the second millennium BCE, contributed to the expansion of trade. At about the same time, the development of new techniques for irrigation (falaj), created the breeding ground for increased food production, which facilitated more permanent settlement both on the coast and in oases inland. This took place in the Iron Age, circa 1300–300. It was during this period that written language was used, with a Southern Arabic alphabet. Contacts were established with the Assyrian and Persian empires.

The first known coins from the area date from around 300 BCE, from the Mleiha period, after a successful trading town of the same name. From this time, there are traces of extensive imports of goods from Greece and southern Arabia. The use of horse stems started at this time. Trade routes were developed and strengthened in the later centuries, paving areas on the Gulf of Persia to the Mediterranean – as well as to the East. At the beginning of our time, there was trade with the Roman Empire and Mesopotamia and Babylonia, as well as with India

Christianity was introduced to the area in the 6th and 7th centuries. Subsequently, Islam was introduced from around 630, which meant a watershed in the area’s history, and which has also helped to characterize the FAE in modern times.

Al Qusais pot, from the first century BCE, exhibited by the Dubai Museum (Al Fahidi Fort).

Later history

The more recent history of today’s FAE can be linked to the introduction of Islam, and the later establishment of European trade interests in the region. From the 6th century, Islam has been instrumental in shaping the communities of the Arabian Peninsula, rooted in tribes that settled on the coast and established the Sheikh empires that in 1971 joined the FAE federation.

The introduction of Islam

The introduction of Islam into the FAE occurred from circa 630, after envoys from the Prophet Muhammad found their way to several communities on the shores of the Gulf of Oman and the Gulf of Persia, and handed over letters inviting local rulers to join the new faith. For the later FAE, Islam came from today’s Yemen and Oman. After the Prophet’s death in 632, rebellions (the Ridda wars) broke out, among others, in the market town of Dibba in today’s FAE – and the victory of the Muslim forces there laid the foundation for Islam’s foothold and expansion in this part of the peninsula. In the following years, Christmas Father, a successful trading center whose historical location is unclear (became a later Christmas father, Ras al-Khaimah), used as a starting point for the Islamic invasion of Sassanid Iran (637), secondly by the Abbasid invasion of Oman (892).

From archaeological excavations, traces of settlement and business from early and later Islamic periods have been found across much of today’s FAE, including on islands in the Gulf of Persia.

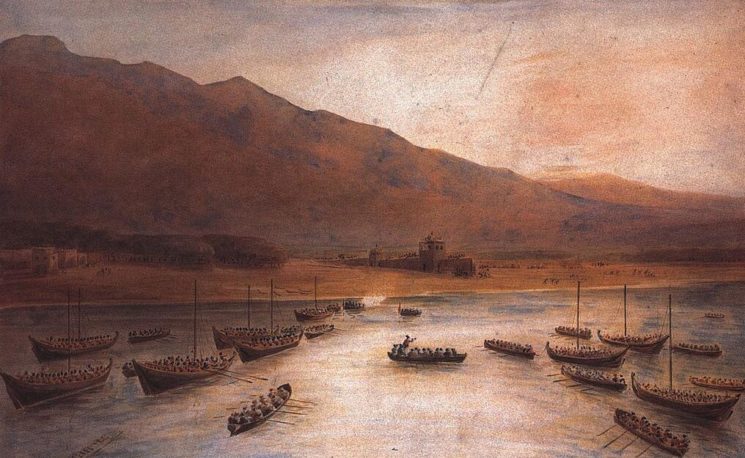

Painting depicting the British fleet anchoring off Ras Al Khaimah in 1809.

Foreign entry

Several European maritime nations competed to take part in trade with the East, after Vasco da Gama found the sea route to India with the help of navigator and cartographer Ahmad ibn Majid from Julfar. Parts of the area were then, from the 1300s, controlled by the kingdom of Hormuz. The entry of Portuguese, and later British, into the arena helped change the power relations in the region from the early 16th century.

European states sought control of the growing trade in the region by establishing trading stations along the coast towards the Indian Ocean, and building defense facilities on the coast of the Arabian Peninsula as well. When Portugal came to the area as the first European state, there were several successful trading towns on the Iranian side of the Gulf of Persia – inhabited by Arab tribes; on the Arab side, there were several smaller cities.

In 1506 Afonso de Albuquerque sailed into the Gulf of Oman and the Strait of Hormuz. At this time, Christmas Father in today’s Ras al-Khaimah was subject to Hormuz, which was then one of the foremost trading centers in the area. The Portuguese built a fort at Christmas Father and linked the city to its trading network, which included Hormuz and Goa, Malacca and Macau, before being driven out of Arab tribes in the mid-17th century. Portugal built a number of fortifications along the coast, competing with the Ottoman Empire for influence over the area in the 16th century. The Ottoman Navy fought against the Portuguese forces in the Gulf of Persia, and the Portuguese were defeated by Dutch and British naval forces in 1625, and then established a temporary base in Ras al-Khaimah, where they built a fort at Christmas Father in 1631. With Portugal’s influence weakened, there was a rivalry between English and Dutch trading houses for control of trade in the area. At the same time, the Persians sought to regain control on their side of the bay, while Oman took control of Bahrain and other areas of the Gulf of Persia.

The arrival of Europeans coincided with the emergence of the Qasimi Empire (also known as Qawasim), named after the dominant tribe Qawasim, in the 18th century. A group of Sheikhs established a state formation with economic and military strength in an area that is now covered by Ras al-Khaimah and Sharjah. It controlled fisheries and trade in pearls in the Gulf of Persia and out into the Indian Ocean, and opposed foreign attempts to take control of the trade. The Qasimi dominance of the Musandam Peninsula was challenged by the Sultans of Muscat. The United Kingdom was initially only interested in the Persian coast of the Gulf of Persia, where representatives of the British East India Company had established themselves, essentially to promote the export of textiles from India.

After Qawasim lost power, a confederation of tribes, Bani Yas, in Abu Dhabi emerged as the dominant in the area, after the al-Nahyan family in 1793 moved there from the oasis al-Liwa. While Qawasim was a strong sea power, Abu Dhabi’s power base was land-based, with limited coastal settlement, partly due to lack of fresh water.

From the early 18th century, British control of trade was challenged by Qawasim, which established a competing trading center on Qishim Island, and controlled the entrance to the Gulf of Persia – from positions on both sides. Attacks on merchant vessels, including British ones, led Britain to ally with Oman in 1798, and then launched an expedition to bring the pirate business to life. Qawasim’s fleet was destroyed after several strikes in 1819. Although the area was long known as the Pirate Coast, questions have recently been raised about both the scale and nature of the business, while combating piracy may have been a pretext from the UK to secure control of the area – as part of protecting its growing trade with India. Both France and Germany, in addition to the Ottoman Empire, was from the second part of the 19th century looking to strengthen its influence in the region.

British protection

Qawasim’s defeat enabled the United Kingdom to regain control of the area by entering into separate agreements with nine Sheikhs in 1820 to fight piracy. The Sheikhs thus saw an opportunity to restore stable conditions for their board and their trading activities. The agreements were signed with the British government in Bombay. While the Sheikhs had entered into an agreement with the United Kingdom, they had also regulated the relationship between themselves, as a basis for increased stability. Britain’s contractual protection of rulers, for example, was expressed in 1938, when there was a conflict between Dubai and the country’s trading position in Dubai.

The treaties were followed by new agreements with the rulers of Sharjah, Dubai, Ajman and Abu Dhabi in 1835, which regulated conditions related to the pearl fishing season. Subsequently, a more comprehensive agreement was signed in 1853 on the introduction of perpetual maritime weapons, after which the area became known as the ‘Trucial Coast after the English word’ truce ‘. Subsequently, a new series of agreements were entered into in 1892, after which the emirates became known as ‘Trucial States’ (also called Trucial Oman). Ceasefire and stability should be ensured through British military power – at sea and on land, and the UK should help resolve conflicts between local rulers as well and protect them in the event of internal turmoil. Sheikh undertook not to relinquish parts of their territories, or to enter into agreements with states other than the United Kingdom without British approval. They also pledged to fight slavery that was still common in the area in the 1880s.

The treaties of 1892 safeguarded Britain’s interests without formally making the sheikhs of British protectorates, but at the same time helped to link the emirates more closely, while at the same time clearly appearing as their own state formation. The agreements also tied them to Britain when World War I broke out, preventing other countries from establishing military bases along the coast.

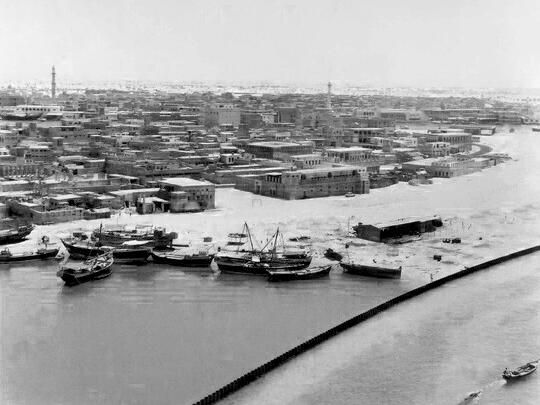

The historic al-Ras district of Deira, Dubai, in the early 1960s before revenues from oil extraction changed society, among other things, with extensive development of modern infrastructure.

The beginning of the oil age

As oil was discovered in other parts of the region, all rulers of the treaty states signed an agreement not to grant oil licenses to companies that had UK support. In doing so, the United Kingdom secured further control of oil extraction in the Middle East. In the 1930s, oil exploration agreements were signed with several companies, and these should lay the foundation for the biggest changes in the area’s history in the coming decades.

Through the agreements of the 19th century, Britain had indirectly assumed a police role in the Emirates, and after World War II intervened in a military conflict – and set the border – between Abu Dhabi and Dubai (1945-48). In the period leading up to independence, there were several conflicts over border demarcations – accelerated by oil exploration, with demands for clear borders and rights. Such a conflict also arose between Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia, including the Buraimi oasis, accelerated by possible oil deposits. Saudi Arabia sent forces to the area in 1952, and negotiations at a 1955 Geneva tribunal failed to advance, with military forces from the treaty states, with political support from the United Kingdom, occupying the oasis. A smaller military force, Trucial Oman Levies (later Trucial Oman Scouts), and substantially consisting of Omanes, had been established in 1951 for use throughout the area. In 1956 and 1957, Dubai and Abu Dhabi established their own police forces; several of the sheikhs began to establish military forces in the 1960s. A council of members from all the Sheikh tribes met every other year from 1952 to discuss administrative matters of common interest.

Investments in oil exploration in the 1950s contributed to the development of the infrastructure, and with revenues from the extraction and export of oil from 1962, it was further invested in a social development that further linked the Sheikh resources. Among other things, this was rooted in a five-year development plan for the period 1956-61, with the development of health and education systems. A separate development office was established in 1965. Oil deposits changed the economic outlook after the important pearl industry experienced a crack in the 1930s, partly as a result of the depression, even more so after Japan introduced the cultural pearls that far out competed the pearls of the Persian Gulf.

Arab nationalism gained a foothold also in the emirates of the Gulf of Persia in the 1950s, and attacks were made against members of the ruling families and British targets. Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser pledged financial support if the Emirates broke ties with Britain – prompting the British to favor the establishment of a federation.

In 1968, the United Kingdom announced that it would withdraw from the Treaty States in 1971, on the basis of financial priorities. The sheikhdom of the Gulf of Persia then began a process of establishing a confederation. Bahrain and Qatar chose to stand outside; seven other Sheikh judges joined forces to form the United Arab Emirates.